In December, AORN co-hosted a webinar with CONMED led by Jennifer Pennock, Associate Director, Government Affairs, AORN, and Erin Kyle, DNP, RN, CNOR, NEA-BC, Editor in Chief, Guidelines Perioperative Practice, AORN.

They highlighted legislation progress around the U.S., and shared guidance on advocating for a smoke-free OR. Here is a summary of insight, questions, and answers from this engaging session.

How can we best explain surgical smoke to someone hearing about it for the first time?

Here is a simple, three-step process:

- Identify the problem: Surgical Smoke

- Describe how the problem affects you: Health effects and Impact on quality of life

- Present the solution: Evacuation of surgical smoke

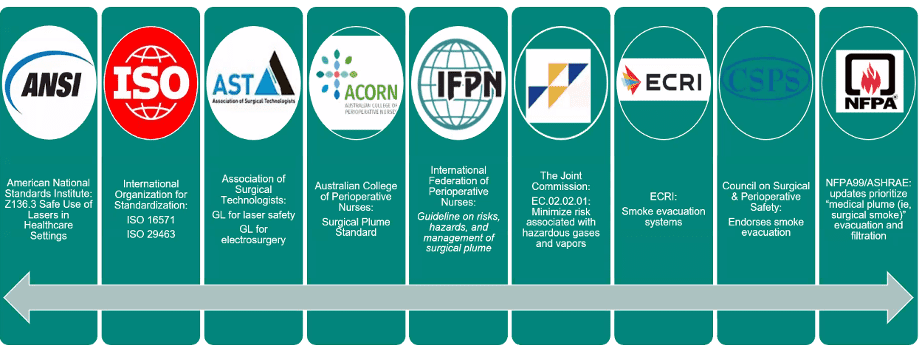

Who supports surgical smoke safety?

Numerous organizations, shown below; a number that’s grown from the first time surgical smoke was discussed in the literature in 1976.

Support for Surgical Smoke Safety

Our hospital has a surgical smoke prevention policy, and we do have surgical smoke evacuation devices, but in general this is not followed. What can I do to get support from all stakeholders to follow the policy?

The best thing to do first is get the support of your department leaders and come up with a plan to do some intensive education about the dangers of surgical smoke exposure. Include everyone who works in the perioperative area. CONMED provides a continuing education course on surgical smoke plume worth 2 credits for RNs and STs! Click the link below to request the CE course today!

The Guideline for Surgical Smoke Safety details the research about the health dangers of surgical smoke, and we have found that when people who work around surgical smoke really understand just how dangerous it is, they become much more motivated to protect themselves.

Many perioperative team members who have worked in the OR for many years (and have breathed surgical smoke for years or sometimes decades), might be reluctant to admit to themselves that their long-term exposure might actually be a problem. It’s important to be sensitive to this, and at the same time present the facts that are detailed in the research.

Once you have the support of your leaders and a plan for education, it is time to ride the momentum and Clear the Air®! CONMED can support you every step of the way.

Any suggestions for getting physicians and other staff on board and championing smoke free ORs, even without a mandate?

A good first step is to identify the surgeon(s) in your practice who you would consider most open to learning and willing to review the research about the dangers of surgical smoke. Physicians respond to scientific data, and this is almost always the best way to get their attention!

Then ask that surgeon (now your champion) to help you with educating others by connecting them to the physician who is the designated leader of the surgery department. Make it easy for them to present the information to their colleagues by giving them the tools available through AORN (i.e., Guidelines, Toolkits, Go Clear Award) and CONMED (Infographics, Videos, CE Course).

As mentioned in a previously answered question, make sure to proceed with sensitivity if you are talking with someone who may have been working in the perioperative environment for many years, and may have been exposed for a significant amount of time.

Is the use of medical surgical suction OK for small amounts of smoke with an in-line filter vs. using a smoke evac system? Is this adequate to capture all smoke if the inline filter is protecting the suction section vs. the caregivers?

The AORN Guideline for Surgical Smoke Safety makes recommendations for surgical smoke evacuation and filtration which includes this excerpt:

2.2 Use a smoke evacuation system (e.g., portable smoke evacuator with filtration, medical-surgical vacuum with an in-line filter, centralized stationary smoke evacuation system) to evacuate and filter all surgical smoke. [Recommendation]

2.2.3 A medical-surgical vacuum system (i.e., wall suction) with an in-line ULPA filter may be used to evacuate small amounts of surgical smoke as defined by the health care organization’s policy and procedures. [Conditional Recommendation]

Low suction flow rates associated with medical-surgical vacuum systems limit their efficiency in evacuating surgical smoke, making them suitable only for the evacuation of small amounts of smoke.1-4

The AORN Guidelines are written to be applicable to all practice locations where operative and other invasive procedures are performed, including those with limited resources. Some facilities struggle with access to the most basic needs and in these locations, it is better to have a medical-surgical vacuum system with a filter than nothing at all.

But there are limitations to the effectiveness of medical-surgical vacuum systems for surgical smoke evacuation. Organizations may choose to include in their policies which, if any, procedures in their organization might qualify as producing a small enough amount of surgical smoke that the medical-surgical vacuum (with ULPA/carbon filter) system may be used.

Long answer short... the best evidenced based practice is to use a smoke evacuator during every procedure that generates any amount surgical smoke, and that is also the recommendation that should be reflected in the wording of the policy.

If you are looking for more information on surgical smoke, visit www.everybreathmatters.com.

To request a Surgical Smoke Management CE course for you and your colleagues, click here.

1 Control of smoke from laser/electric surgical procedures (DHHS [NIOSH] Publication No 96128). The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 1996. Accessed August 30, 2021. [IVB]

2 Ogg MJ, Johnstone EM. Clinical Issues–June 2017. AORN J. 2017;105(6):619–627. [VA] [PubMed: 28554359]

3 Smoke evacuation systems, surgical. Device Overviews & Specifications - Comparative Data. https://www.ecri.org/components/HPCS/Pages/Smoke-Evacuation-Systems,-Surgical.aspx [subscription required]. Published 1/1/2020. Accessed August 31, 2021. [VB]

4 Ball K. Protecting patients from surgical smoke. AORN J. 2018;108(6):680–684. [VA] [PubMed: 30480798]